Document of the Month

Welcome to the Collection Showcase section of Warwickshire's Past Unlocked. On this page you can explore some of the interesting and important documents that we hold at Warwickshire County Record Office and learn about the historical background to their creation.

Each month we will highlight a different Document of the Month and display links to PDF copies of the previous 12 months documents for your enjoyment.

For earlier editions of Document of the Month, please see our archive.

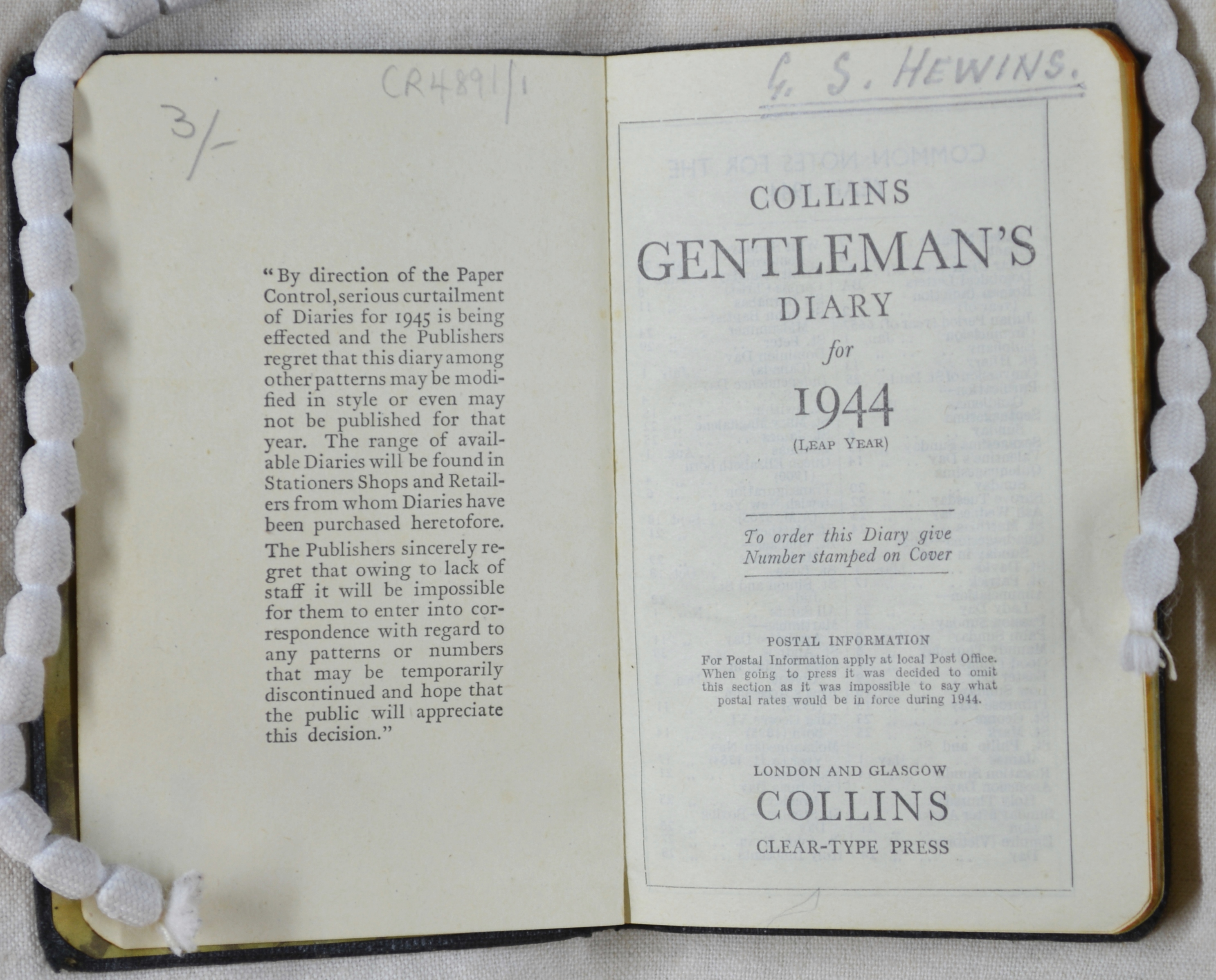

Rev. G. S. Hewins' Diary

For May’s Document of Month, we are looking at the pocket diary of Rev. G. S. Hewins for the year 1944. Hewins was the Rector for Oxhill, Warwickshire between 1940 and 1944. Looking at the entries you get a sense of the “every day”, with the mentions of the weather and the general goings on in his day-to-day life.

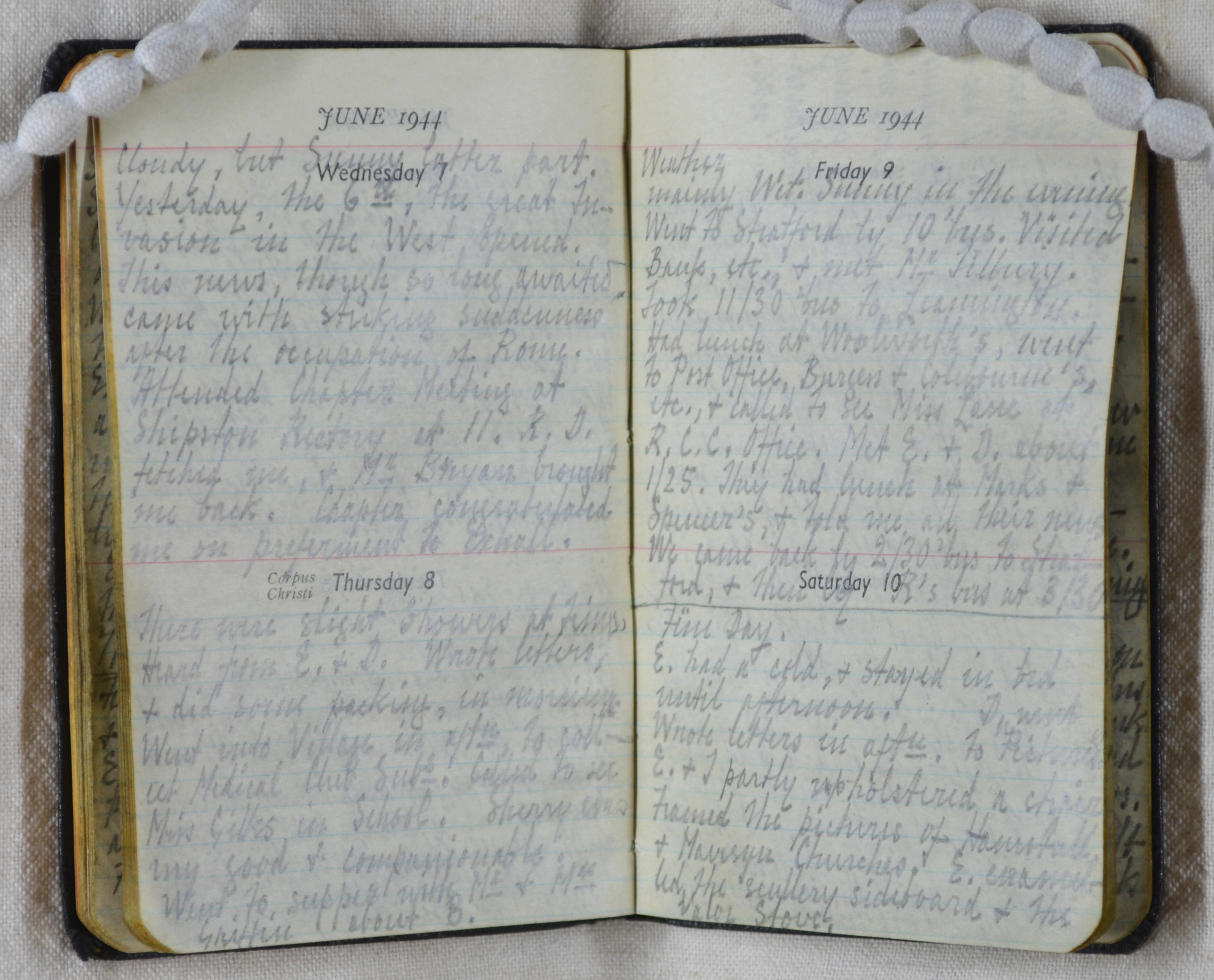

Here are some entries from his diary. A transcript by Ann Hale is also available at CR4981/2.

/Reverend G.S. Hewins’ Diary

Warwickshire County Record Office, CR4891/1

‘Dr Wells called in the morning. The Italians were engaged length of brook adjoining the orchard. Mr Price gave me 2 bundles of large envelopes. Read some of Arthur Mee’s volume on Worcestershire.

Friday 18th February Very cold and Windy, with slight Snow

Heard from my dear Mother that arrangements had been made for her to go to Shiffnal (sic) Hospital on Saturday morning the 19th, to be examined by a specialist. I hope and pray that all will be well. Dinky’s party for the Land Girls took place in the school at 7 & was very enjoyable. A good tea was followed by games, etc.

E. had a Birthday Gift of Stocking from Teddy, who also returned the Watch, repaired. We were very busy in the morning. Wrote several letters in afternoon. The News came through that Rome was occupied yesterday by the Forces of the United Nations.

Yesterday, the 6th, the great Invasion in the West opened. This news though so long awaited came with striking suddenness after the occupation of Rome. Attended Chapter meeting at Shipston Rectory at 11. R.D. fetched me, & Mr Bryan brought me back. Chapter congratulated me on preferment to Exhall.1’

You could almost believe there wasn’t a war going on, apart from a few entries which mention Italian prisoners of war (most likely from the POW camp in Ettington, who were sent to work in the fields) or the Land Girls. But they are still talked about in an everyday tone. Plus, there are single line entries mentioning the occupation of Rome and the start of the Normandy Landings. These all give a good look at life on the Home Front, carrying on as best they could under the circumstances, and the reminders of the war going on both at home and away.

Land Girls

The Women’s Land Army (also known as Land Girls) were women recruited from towns and cities to do a variety of jobs on the land, working in all weathers, conditions and any part of the country. More information about them can be found on the Imperial War Museum’s website.2

Reverend Hewins

Geoffrey Shaw Hewins was born 26th October 1889 in Codsall, Staffordshire to Alfred John Hewins (1863-1940), a landscape painter, and Anne Louisa (1863-1945). In 1913 he obtained a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Wales, then attending Lichfield Theological College, before being ordained deacon in 1914 and a priest in 1915. During the First World War, he served with the Y.M.C.A in Salonica as a Church of England Minister. He married Elsie Vera Abraham in Market Drayton, Shropshire, having a daughter Vera Agnes, born 21st February 1933. He became Rector of Oxhill from 1940 until June 1944, after which he moved on to become Vicar of Exhall.3

He carried on writing in his diary, his last entry being on New Year’s Eve 1944.

During the war, those who stayed in Britain had to live their lives as best they could, whilst dealing with the hardships of life on the Home Front. Records such as diaries like this one are a great resource for understanding the way of life of those at the time.

References

- Rev Geoffrey S Hewins' diary, by Ann Hale, Oxhill, Warwickshire County Record Office, CR4891/1.

- Imperial War Museum, Land Girls (accessed 01/04/2025).

- Biographical notes on the life of Rev Geoffrey S Hewins by Ann Hale, Oxhill, Warwickshire County Record Office, CR4891/3.

Please click on the links below to view PDF copies of previous Document of the Month articles (opens in new window)